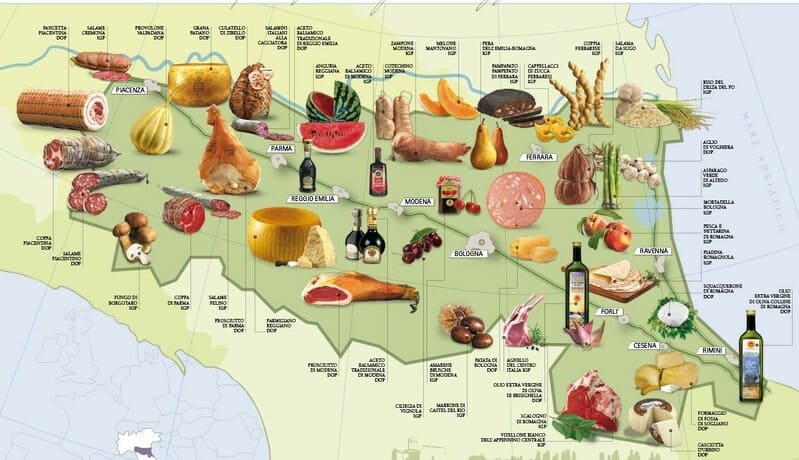

Well, the truth is that in Italy, we do not. Vegetables, herbs and fruits have a terroir, and even meat. You go to sicily for the best lemons, to liguria for the best (and only) basil, to tuscany for a "fiorentina" steak (made with meat exclusively from chianina cows) and to piedmont you expect nothing less than a fassone steak (another type of cow). But you also know the "sandaniele prosciutto," the "prosciutto di Parma," right? These are names of towns locations in Italy because the product is tied to that region and sometimes the region is very limited. Here is an example of the products that are protected by Italian legislation, meaning that the name of the product can be used only if produced in these regions.The reason behind this legislation is simple, really: the characteristics of the land, the climate and the processes that go into growing the principal ingredients for that product are unique and they contribute to the quality of the final product and they cannot be reproduce by just copying the process. That is why you have not tasted pesto until you get the one from liguria, your dishes will be wildly different even when you use the same recipe depending of whether your oil comes from liguria, umbria, toscana, or greece. Since we are used to think of differences in terroir for wine, extending this to fruits, vegetables, and herbs may make logical sense, but people often have problems stretching this thinking to meat. So let's ask the question, why should a pig raised in Vermont be any different from one raised in Ohio? Well, there is absolutely no reason for a difference if they are both kept in confinement inside a building and fed conventional feed that is grown in the midwest and shipped around the entire country. But, the moment you take this pig outside the moment you change the diet to incorporate more the herbs, nuts and grasses that are traditional from one area and the moment you vary the breed, you have several reasons to expect different flavors from the same cut even when processed the same way. The differences may be less notable with fresh meat, but when you use curing and aging, all the flavors become concentrated (the meat loses between 32% and 45% of the water from fresh to cured). Breed has a profound effect on flavor, so couldn't we just move a pig like the cinta senese to Vermont? Yes you can do that, but this breed of pigs has evolved for hundreds, if not thousands of years to adapt to the environment and climate of tuscany. How well will they do after the 20th day in a row they are at -20F temperature? How much stress will that cause? And why bother? Why not exploring the flavors of the meat from animals that have adapted and strive in this area? Feed: feed is one of the most important factors when you comes to flavor in the meat. Most feed options on the market barely even tell you the ingredients, they just talk about protein and energy percentage. The bulk of commercial feed includes soy (for proteins) and corn (for energy) plus traces of minerals and supplements. When you buy a pork chop at the store, you are basically eating a modified version of the corn and soy flavors. Why should you be surprised of the bland, uninteresting flavor? Just look at the thousands of recipes that require the most wild combinations of spices and processes basically to introduce something interesting to an otherwise bland meal. Variety of feed is as important, or even more important than nutritional content of the feed ration when it comes to flavor. Interestingly, when we talk about variety in feed, we also talk about PASTURES, and this is where the final product becomes embedded with the land where it was produced. Pastured raised pigs: unfortunately this means different things to different people. To some, "pastured" simply means "not inside a building." Some pigs are raised on a piece of dirt and have never seen a blade of grass in their lives. Is this type of farming better for the pigs than being raised inside? Agronomists argue it is not and actually identified it as worse because you cannot clean the area that becomes covered in manure and a breading ground for bacteria. For us, and many other farmers, raising pigs on pasture means making sure pigs have access to fresh grass, they get to graze and also, inevitably, dig (some a little some a lot). When they chomp on the grasses, wild fruits and all the goodies offered from the land, these flavor become part of the profile that we will find again on our plates. One farm may be located in an area richer in herbs, another farm may have more wild grapes, others may have specific types of nuts (we have hickory nuts on our land). There is the potential for a map of flavors based on the location where the animals were raised. Time: time also has an important role in the development of flavor. If you make wine, you have to collect the grapes at the right time when they are ripe, correct? Well... in a sense it works in the same way for livestock. You need to allow them to chomp and absorb all these flavors and store them away. Do you know that commercial pork is raised for 5 to 6 months before being butchered? Piglets are about 3 lbs when they are born and processed at 220 to 240 Lbs. Achieving this increase in weight in such a short time was considered a major achievement during war time when farmers were given the difficult task to feed the country on few resources. Today, however, given a different situation, this un-natural growth is not needed and we realize now how much we lost in the process. At our farm, for our breeds and diet, pigs take between 12 and 14 months to grow to 220 Lbs. Some of the high quality breeds in Italy take 24 months. So, why am I writing about this? First, because I am truly sick and tired of seeing american butchers expropriating names of protected types of cured meats just because the US does not enforce EU laws. Only few artisanal products are currently protected in the US. For example, Parmigiano (from parma) cannot be used on cheeses made outside of emilia romagna in italy (this is why at the store you find "parmesan"). There is a very laborious process to go through to protect the region of origin of a product, it is not easy and it is not quick. I put below a link that takes you to all the names of DOP products from Italy, there are also products that are IGP (protected geographical region) which means that either the primary ingredients OR the processing needs to be completed in the region and following specific guidelines (for example, finocchiona, either you use the meat from there or you need to be there to make it or legally you cannot claim you are making finocchiona). Here is a complete list updated in 2021... it is long. DOP and IGP LIST Am I just upset about this?

NO, I AM EXCITED, because, this New World I find myself in, is also a completely empty canvass where I hope to discover the special flavors that are tied to different regions. After the first growth plan, where we are basically developing a strong and stable production to support our farm, we will begin collaborating with farms in different regions and make products that are unique and specific to their land. We will not be using herbs and weird ingredients to bring up new flavors, we will just turn to the wonderful biodiversity that is already part of Earth and through this project we hope to support and encourage the protection of biodiversity wherever farmers raise their piggies. If you like this idea, you can be part of our tema and our vision - here is the link to the kickstarter campaign to help us buy 2 more pieces of equipment that can help us grow.

1 Comment

Ever wondered what pigs do all day long in the winter?

In the winter all our work is confined to the barn’s walls. It can be pretty boring for our tenants and especially for the pigs. Sheep seem pretty content. Chickens are the masters of the barn and can go wherever they please, so they are thrilled (I will write later about happy chickens … it is a topic that deserves its own space). Pigs, on the other hand, become very needy. It takes twice as long to shovel the pig pens because they are all so needy! The early risers are super eager to come and chat - I swear, they come and talk to you! I am quite familiar with pig noises, and can easily distinguish their communication. They make specific sounds to communicate: I am hungry, I cannot believe you fed him before me, I am in pain, you are bothering me, I am going to eat you, I am scared. Moms also say: lunch is served, follow me, and of course if you touch my child you are meatloaf. But in the winter mornings, it is none of those; it is truly a full-on conversation. Sometime I wonder if they are telling me their dreams, because those are long conversations and if you bend over and look at them in their eyes they go on and on and on and I am pretty sure they are telling me something. And some of them have very long dreams and take for ever! Much longer that you have time for, especially if it is cold and the only thing that can keep you warm is shoveling. But, yes, some pigs come over and want to chat – they are bored. And of course, we chat back, in pig-gish. Stefano is the best at the farm in pig language. I am fluent in understanding but only intermediate in speaking. I can communicate I am afraid and I am going to eat you, but the rest is pretty hard. The pigs have also learned to understand some Italian, they know “go,” “go away” and “stop that,” but they are quite horrible at speaking Italian. After they are done talking, they want to be scratched and do not dare forgetting that this one likes the belly by hates if you touch his head and vice versa for the next pig. If you forget… they will let you know. How about ignoring them to shovel, so you can go on with the chores? They know how to perfectly position themselves so that you have no alternatives but to scratch them. As soon as you are done with petting one, another one gets up and wants his share… it never ends! Some pigs care less about being petted or coming over for a chat and look for other types of entertainment to help the day being less boring. Giuseppina, in the group of the sows, loves sticks. I have found her a few nice, sturdy wooden sticks over winter that she really likes. A first I found her some thin dry burdock stalks and she was almost offended by my choice: she picked up the stick and put it right on top of the manure pile I was shoveling out of her pen… I thought that was an effective communication technique. The sticks she likes, she will carry them around. Sometimes, in the morning, she brings them to me, if I am working in her pen. She does not want me to take them from her but if she puts it down and I move it, she will pick it up and put it back to the same spot. Other times she spends quite a bit of time to figure out how to push the stick through the fences to the group of pigs next door. It is a long stick so it does require some concerted effort from pigs on both ends. At times we find that stick in locations that I swear I have no idea how they did that. Some of the neat pigs (yes some pigs are very clean and neat, and others are filthy – just like humans) organize all their throughs in a pile. I have no idea how long that takes them and how they do that. I never witnessed anyone in the act. For a while, I believed it was the farm assistants and I started asking them why on earth they would organize the pigs’ throughs in a pile, and that is when we all learned that it was the pigs. Other pigs are less creative and they find endless entertainment dumping their water on the floor. Probably because they have figured out that this leads to a flourish of activity and loud noises and weird accents from the farmers – these are indeed the situations when our farm assistants learn Italian. Following, of course there is an effort from the farmers to make a modification to the through design to outsmart the pigs and make it impossible to flip the troughs; but every time we make an improvement on the design they respond “challenge accepted.” I have started to believe this is a sort of pig version of chess. So far, we are ahead of the game in most pens but there is one that we are constantly getting checkmates, and indeed there is an ice-skating rink in front of their pen, which I am sure adds to the entertainment because of the numerous chickens falling as soon as they touch ice. My favorite type of pig entertainment activity is what you can see in the pen of the Giocondi. Gioco means game, in Italian, so Giocondi means “playful ones.” They absolutely love hay and every time you give them hay, it is the VERY BEST day in their lives, even if you just gave them hay 2 hours before. They pick it up with their mouths and shake their heads as hard as they can, they move the hay from one corner to another and then back again, they take a big mouth full and try to convince their siblings to catch them to get the hay, they roll in it, they make little 360 degree jumps making the hay fly everywhere, they borough in it… It is just the best thing ever. It reminds me of the way life was simpler when I was a kid; when the best thing on Christmas day were the boxes and the ribbons around the presents, and I cannot help to smile knowing that feeling and seeing them going through that excitement every single time. Lambs – while some lamb left the farm, right now new baby lambs are popping right and left (although they are arriving 2 months earlier than expected). Right now we have 5 (from 3 of the 40 ewes) but it already feels a better lambing season than last year. In 2020 we experienced very out-of-the-world lambing difficulties that caused us to lose several of our old-time favorite ewes – we even called seasoned shepherds in the area and when we described the situation they all scratched their heads because… certain things are just not supposed to happen (mostly in terms of weird positioning of the lambs at lambing time). I feel this year we are at a better start already with the ewes doing their own things and showing the lovely maternal instincts that Icelandic have.

Ducks and chickens – mating has started for the ducks! We have now a nice pool where they can go do what ducks do (and do better in the water) and we have a lovely egg nesting station where they like to hide their eggs. In 2 weeks we will fire up the good ‘ol incubator (dated approximately WWII) and the entire house will be vibrating at the notes of its powerful engine that keeps the eggs at the right temperature - with the small inconvenience of keeping all the farmers awake for the next 28 days for ducks then 21 for chickens and then repeat. So… yeah, no one will be able to sleep for the next 4 months so be weary of very twitching farmers – but who cares… at the end we will have ducklings and baby chicks. It is almost like going thought a “group” gestational period where we (farmers) are the expecting fathers. We may be exhausted and ready to jump at each other throat for the lack of sleep but the moment we hear the first little *cheep cheep* everyone gets big lovey dovey eyes, we all gather around the incubator as one of us reaches inside and a beautiful, perfect, super confused, fluffy chick emerges at the end of a dog tennis launcher – yes you heard me – we use the tennis ball launcher to harvest the chicks from the humongous incubator (here is a link in case you are not familiar with this device: https://petlifetoday.com/best-dog-ball-launchers/). After few seconds of intense oxytocin secretion, we will need to place the little guy back in his new world to keep him warm and by the time the incubator door closes again, we are back at each other’s throat – until someone else says “hey should we check on the chicks again?” WARNING: do not check on chicks a lot or the other eggs will not hatch. Pigs and Chickens. The best part of winter is the symbiotic relationship between chickens and pigs. There is something extremely satisfying in seeing two species getting along well and chickens and pigs are masters of that. In the morning, you can always count of a few chickens dozing off on top of a pile of pigs. The chicks keeping their feet warm and the pigs enjoying the new down comforter. The best part though is when you have individual chickens that decide they had enough of the other poultry and adopt a group of pigs as their new group. We have 2 right now. One is a hen that I think has as main motivation the fact that she occupies the warmest, driest, and safest nesting spot in the barn, which happens to be inside the pen of 8 little piglets. She was there first, to tell you the truth, and did not look ecstatic when we introduced her to her new roommates. It took two weeks of determined pecking at the little inquisitive noses before the piglets learned to just cohabit with her. Now, things are comfortable and the other day I even saw her pecking some food from the head of a sleeping piglet. The other “immigrant” chicken is taking on the role of a pig in all aspects. Sleeps with the pigs and even takes her place at the feeding trough. When you look at the cute pink noses all in line to eat at the through, the shiny red crop on top of the hen’s black head makes you do a double take whether what you are seeing is indeed happening. But the pigs seem to not have such concerns and treat her as one of the group, which includes occasional siblings disagreements in terms of sharing food and sleeping spots. GUSTAVO IS LEAVING! (Gustavo is our boar) He will join Bread and Butter Farm on February 26th. They have promised to look after him for at least other 3 years. He will be incredibly missed at the farm, not just from us but I am sure by the girls as well. We are preparing a special basket for him so that farmer Brandon, at Bread and Butter can offer him his special treats once he gets there. We are putting in the basket Yolo popcorns, tortillas from VT tortilla CO. frozen chicken eggs, tomatoes and, of course, a bucket of ice cream from Cookies' Love On the positive side, we have just welcomed Filippo (PIppo for his friends - see Pippo's picture below), our new young boar. He is not quite ready to meet the girls yet. He first needs to grow quite a bit, since he is only few months old. And in the meantime? Well, meet Dr. Ale, our new BS (Boar Substitute). Yes, I will be doing artificial insemination, and I will use all the modern techniques for insemination, including the very informative video from the Netherlands on how to mount a sow to make sure she has a large litter. We may sell tickets to watch this event AH! What does it take to make a salame? Probably more than you can imagine (or want to imagine). You see, the job of the salumiere (the specialized butcher) contributes only in a small way to the flavor of the final product. In fact a good salumiere is humble because his/her work is only marginal compared to the work that the farmers put into the creation of the final product.

PRE-SALAME Making a salame starts in the barn, on cold winter mornings, usually when there is a storm and the experienced and patient sow works to get her piglets out, dry, fed and warm, while we (the human doulas) jump swiftly to remove the little ones from underneath mom in case they are in danger of being crashed. You see, the piglets need the warmth of the mom; they need to be at 100F, but in the winter in the barn is below zero. No matter how much hay and animals are in there, if outside there is -20F, it is too cold for them so they seek mom's warmth but by doing so they are very close to her and a good mom can keep track of 10 or 12 piglets but when it is 14+ it becomes impossible to know where they all are and being able to sit down safely or even turn around in her sleep. So we help out. Some farmers use heat boxes for their piglets but we found that our moms just need us for the first few hours and then at feeding time so we have our system. We also have the support of the hens that, for some reason unknown to me, they start hanging out in the pig pen when new piglets arrive and they watch over the kids, preventing them from wondering away when mom gets up to feed and drink. Salame is made in September of the year before, by the farmers on the tractor seeding the pastures with a combination of grasses, legumes and herbs that will become an essential part of the diet of the pigs when they will forage that area the year later. Salame is made in the hot mornings, in the rainy mornings, in the windy mornings, in the freezing mornings with a weed-wacker in one hand and a roll of wire in the pocket, as we make new paddocks. Salame is made with a bucket of food in one hand, running like crazy through the fields with a dozen pigs running after you while you lead them to the new pasture. Salame is made every saturday when we pick up the expired fruits and vegetables from Shaws and we giggle thinking of the pigs' reaction to avocados, bananas (except for Salciccia, she does not like bananas), cucumbers, papayas and peaches. ALMOST SALAME We take pride in the fact that we process our own meat. A slaughterhouse close to our farm does the slaughtering process (from pig to carcass) then we have a local business deliver the chilled carcasses to our processing facility in Middlebury and there we meet the meat. I know it is unthinkable for many people that I am now cutting the meat of the same animal that I have petted, fed, cared for, but that is my special skill: I am a farmer and I have discovered that I can do that. I can live this dichotomy with peace and with respect (and without having to go to therapy afterwords). So, "trust me I am a farmer" and also the butcher. When the half carcasses arrive we have to lift them up and hang them in the cooler and then the process begins. I always spend time doing a carcass analysis, trying to figure out who is the pig that is now in front of me. Knowing their personality, the fields they grazed, their feed, and their personal history helps me make the link between the meat quality and farming management. I think this is the real secret of our product. SALT and TIME (and a few more things) We use only few parts of the pigs for salame, the rest goes into fresh meat or sausage. The parts for the salame are the back fat and the lean. The back fat is only the very hard fat on the back and the neck of the pig. The quality of this fat is key. The fat cells are what holds on to the flavor; they are what facilitates the curing and the aging process. Recently, farmers describe themselves as a "grass farmers," meaning that all they do, they do to grow good grass which is essential for the quality and well being of the animals they farm. I leave that job to Stefano. I am a FAT FARMER. All I do at the farm is for that hard, snow-white fat that is so precious and a limited resource: the amount of salame we make out of a pig is almost exclusively limited by the amount of fat, we always have extra lean meat. The variance in fat quality is astonishing! A pig was ostracized and pushed away from the group? You have a soft fat, no good - if you use it it may smear and cause a crust in the salame that makes the aging process impossible. Do you have a pig that was always lethargic and lazy or that favored high sugar fruits to grains? You get a yellow fat that will become rancid and leave an acidic flavor in your mouth. Did the pigs escape their paddock and stole the corn from the neighbors' dairy farm (yap, that happens)? Well, now you may have a lower quality fat (and a slightly more irritated neighbor). At the butcher table, a surprising large amount of time goes into selecting the lean meat because it needs to be cleaned of any silver skin (the membrane that wraps every bundle of muscle), tendons, fat, weird membranes etc. It takes me a whole day selecting the lean meat that will fill 800 links of salame. After this your salumiere needs to enter precision mode to its highest. We are measuring spices, salts, culture starters (to promote the healthy bacteria that ferments the meat during the curing process), and nitrates and nitrites (yes they are necessary. No, if used correctly, and if you do not eat 1 salame a day, they are not going to kill you, And NO, celery salt is absolutely horrible to use and you end up with more nitrates and nitrites than it is healthy so stop buying the "no nitrates" cured meat, it is only a marketing scam). These products are all very important: the amount of sugar we put in the meat will feed the culture starter which will be responsible to lower the pH and will contribute to the flavor. The amount of salt will facilitate the desiccation (the movement of the water from inside the link to the outside), which is key to have a safe and tasty product. Too much salt will make the product very dry, and very salty. Not enough and your product may not loose enough water and may rotten. Do you remember that FAT we talked about earlier? Fat repels water so the water trapped into the lean meat will be pulled out of the link through this web the fat has created so the size and the consistency of the fat determine the speed at which the water leaves the link and therefore the aging process. . After the grinding and the mixing of the lean and fat with the spices and other ingredient comes the part that is truly a long lost skill. We hand tie our salame. The casings are first stuffed in long links (about 6 feet long), and then one of the three salumieri on duty makes sure the pressure inside the link is just right: not enough pressure and air pockets create (air pockets = bad product); too much pressure and the link explodes and you have to start again. Then, with few complex and swift moves, links are tied in columns of 4 with a hand held spool of a sturdy twine (imported from Italy). Stefano loves this part of the process. We use a technique that was passed on to us by the grandson of a salumiere in Turin and we usually put on some traditional folk Piedmontese songs as we try to master this old tradition. It takes us a whole day to do 800 links (but we hope to get faster!). TECHNOLOGY Till now we have talked about simple processes that required attention and care but not much technology. But after that link is ready for the three phases of the curing process (dripping, curing, aging), then we enter in the XXI + century. We have purchased state-of-the-art curing cabinets from the best curing technology company in Italy. It controls humidity, temperature, air flow and resting times to the second. The food processing inspectors love to spend time looking at our machines and they have told us we have the most sophisticated system in Vermont. These cabinets are our jewels. And like with everything that is that sophisticated, we have a love-hate relationship with them. You see, I learned to make salame from a very old timer, who would start a fire at the end of a cave and then move it to the other end based on the way the meat was behaving. He would open a small window and block another one if he knew the wind from the East was coming, but would open both if the rain from the West was approaching. These cabinets work nothing like what I learned so Stefano and I had to re-learn. We had to read the meat and figure out that wind from the East actually meant to slow down the humidifier, increase the temperature and do exactly the opposite of what the wind actually did. We look and check on these little guys (the 800 links) every day during the sensitive time (the first week), and then the program takes them to the aging process where they will sit there until they feel they are hard enough (usually 5 weeks) and they have reached the right aging. At that point we select 3 random samples (okay... more like 7 since we end up eating a few now and again) and we send them to the lab where they are tested to confirm that the product is safe and does not have any pathogen. By the time the lab gives is the results, we already know because we have eaten so many of them that our digestive system would have known :). In Italy we never sent any salame for lab tests. This process is over 1,000 year old and, if the fermentation is done correctly and the pH is right (which we know by the 4th day using our pH meter), then the product is safe. In the US, the inspectors rely more on lab tests than the process. After the okay from the lab, the okay from the State Inspectors (or the Feds, depending), and the okay from our quality control team (the farmily who eats too much salame for its own good), it is time to spend two days wrapping and labeling the salame. And this is how the product comes to you. Hello fellow humans! Just a quick update on the products and services we have available at this time. We are living through a strange moment in history, but we are armed with so much hope and determination that right now we are just in getting stuff done mode. We are ecstatic and humbled to be able to continually offer the highest quality products to our community and are endlessly appreciative of your support!

Below you can find some of the ways we are meeting the needs of our customers during this global pandemic. In addition, we have adopted a safety protocol in accordance with CDC guidelines to ensure the utmost health and safety of our products, customers and team. HOME DELIVERIES WHERE AND WHEN: We do home deliveries to Addison and Chittenden Counties on the weekends (Chittenden county on Saturday and Addison county on Sunday). We make deliveries from 1-6pm. ORDERING: Place your order here. If you are ordering just meat pies and/or pasta, you can pay directly through our website with paypal. If you order our pastured meat (pork, lamb, chicken, duck), we will send you a text with the exact amount of your order total before drop-off. All orders must be placed by 8am on day of delivery. Because our meat products weigh different amounts, prices on our website are estimates. DELIVERY AND PAYMENT: When we are in the vicinity of your address, you will receive a text detailing a precise drop-off time. We ask that you leave a box or a cooler outside your door (or inside your garage) but please choose a place that allows us to drop off your order without touching any door handles. We will text you the exact total of your order (if you are not pre-paid) around noon of the day of delivery so that you can leave a check in an envelope in the box or cooler you have selected for us. You can also leave cash, but we request exact change in order to respect social distancing guidelines. If paying by card is easier, let us know and we will send you an invoice via paypal. DELIVERY FEES: We charge a $5 delivery fee on all orders under $40. Free delivery on all orders over $40. OUR DELIVERY PRACTICES: We are strict about maintaining social distancing and appreciate you for respecting our choice! Because of this, we do not hand packages to our customers, but rather leave them in boxes or coolers on their doorsteps. We do not use gloves but we do wash our hands with water and soap between each delivery. WHAT IF YOU DO NOT HEAR FROM US BY FRIDAY EVENING? Please check in with us at [email protected]. This online order and delivery system is new to us and we are farmers, not professional dispatchers, so we are learning a new skill! We may mess up orders the first few weeks we try this, but we very much appreciate your patience and continued support. And please do help us figure out our glitches. THANKS! AVAILABLE PRODUCTS PORK Boston Butt Steaks (quick and yummy to cook, cook them as if they were pork chops): $12/lb Boneless Chops: $9.85/lb Bone-in Chops: $9.75/lb Sausage: $10.50/lb Salame: COMING VERY VERY VERY SOON! LAMB Leg: $15.50/lb Shank: $12.5/lb - OUT OF STOCK Shoulder: $14.00/lb Neck: $11.00/lb Rack: $21.00/lb Chops: $18.25/lb Breast: $7.25/lb MÈMÉRE'S MEAT PIES Traditional meat pies - slow-cooked pork, potatoes and onions. This is the traditional recipe of a French-Canadian/Vermont family. Mémère (the grandma) still resides in Bennington and her grand-daughter is the baker behind this beauty. Delivered hot and ready-to-eat! Small - 3.5 inch: $6.50 Medium - 7 inch: $9.50 SAUSAGE HAND PIES These special hand pies contain a delicious blend of our pasture-raised savory sausage, local ricotta, and different vegetables each week depending on availability. Sometimes it's an earthy red pepper sauce, sometimes it's zucchini and herb! Delivered hot and ready-to-eat! $4.50 each PASTA Tagliatelle (homemade egg pasta) - cook in 4 minutes: $3.5 for 1 portion (~110 gr) Ravioli (homemade dough filled with ricotta and veggies): $5 for 1 portion (~ 110 gr) SWEET PIES - coming soon! Italian and American traditions meet in this apple and cinnamon pie. The crust is made with butter and our pastured lard, so this is NOT a vegetarian dish. Small - 3.5 inch Medium - 7 inch PLACE AN ORDER To place an order go to our online store. If you have questions about the ordering process, get in touch on our contact page. Thanks for your continued support! The Agricoli - Ale, Stefano, Bobby, Gaby, Eva, Katie & Diane

An update from the pigs: They are hot. Here is a pig that found on a creative way to use his water trough. Chilling his bum. By the way, this is a red pig with a white band.. these days they all look the same! They use the mud to keep cool because they cannot sweat. gs are well into the rhythm of rotations and have got the hang of moving from a pasture to a new one. They get so excited when you open a new pasture, especially if the new place has different herbs and trees compared to the previous one. The picture below shows a group of pigs that just entered their new paddock. They were chomping on those plants like you would not believe. If you look carefully, in the background, you will see strands of ripe winter rye. We seeded the rye last year and now the pigs are doing a decent job at harvesting the grains. There is an unexplainable satisfaction in seeing pigs harvesting their own food straight from the land. A month ago we seeded one of the fields with special legumes and vegetables for them. The plants and grasses are coming up strong and happy – I can hardly wait for September when this field will be ready for them! I take pictures!

of For what concerns the sheep, we are proud (and surprised) to announce we got 2 new lambs in July! Appropriately named Giulio (july) and Tempesta (storm) – they were born during a rain storm and we found them all wet under mom in the meadow. I am getting ready to say goodbye to Asiago, our ram. We are looking for a new farm for him. He has been with us for three years and for genetics reasons we need to move him out the farm. He is a gentle and kind soul. He will be missed (and he has impressive horns!).

Opening Agricola Meats! Some of you already know we are working on creating our own meat processing facility where we will make cured meats. We are already making some salame at Mad River Food Hub but we are limited by the little space and time available they have for us, the difficulties juggling the slaughtering datres with their limited availability, limitations in the type of products they let us make over there, and high prices. We have been processing our meat there for 6 years bu it is no longer feasible for us. Thus… we put together a business plan to make cured meats in a new facility. We will not only make our own cured meat products but are committed to creating unique products for other 4 farms to create a map of Vermont flavors. Currently we are creating salame for 2 farms and are selling our products in Boston, Vermont and New York. We are not yet in the new facility but things are finally coming together and we can hardly wait to walk into our new place. As soon as we get in there we will be able to start making a variety of cured meats such as prosciutto, coppa, pancetta, lonzino a zillions of other products. We are so excited and ready for this shift! Our hearts also warm up because of the enthusiasm that we find for the project all around us: from the farmers that are happy to finally get a fair price for their livestock and create a unique quality product, from the shop owners that are proud to promote a product in which they believe, and from the people that buy the product and discover a delicious and nutritious way to promote responsible agriculture and be part of the green change that is happening at our farms. It has been a wild and happy ride to get this project going and we have countless people that helped us on the way that we need to thanks... Elizabeth and Fred from Addison County Economic Development, Jim and Cairn from Windham Grows, Omar from UVM extension, Jill from FSA, Dan from VCLF, Lynn Ellen and Diana from Working Lands, Liz from Farm and Forestry Viability Program, Jen from NOFA, Rose Wilson (from everywhere), Annette and Gail from the Women Enterprise Center, Mike Redmond (our neighbour and he can do anything), Tony our future landlord, Carol Degener for branding, Brian from SBDC, Prof. Alberto Brugiapaglia from the University of Agricultural science in Torino. Wow..now that I look at the list (and I am sure I have forgotten someone), I feel so humble that so many people have just offered their time and their expertise and many of them have done that without asking for a compensation, only because they believed in the importance of the project... the importance of supporting Vermont Farms, the importance of supporting a type of agriculture that helps our environment and the importance of creating a top product that can make Vermont proud.

I Just recently I learned about this thing "communal dining" - at first sight it looks like what we are doing. Then I read about it and I read people complaining about it and why they did not like it... I am very happy that we are doing communal dining - even if we are not doing communal dining, actually, let me turn things around, I am going to reclaim the name - we ARE doing the real communal dinners. And here I also argue why if you attend a real communal dinner and you have a negative experience like one described by some food critics, then you are kind of missing the whole point. What is the dining experience at our farm? Well, first of all, we are NOT a restaurant. We do NOT want to be a restaurant and we do NOT provide a restaurant experience. We open our home to a few guests every month and we cook for them and pamper them the way we would with our own guests at home in Italy. We provide a warm, homemade meal. If you are thinking of food like spaghetti and meatballs, lasagna with ricotta cheese and pepperoni pizza you can stop right now. First of all our food is authentic Italian without compromises. When we cook we like to prepare our own puff pastry for voul-au-vent filled with local cheese fonduta and wild morels mushrooms we harvested in our woods. Now multiply that for 5 to 8 courses. Yes, that type of homemade cooking. The food, made with love and respect for what our land and farm provides is only one of the ingredients. The setting is the second secret ingredient. When you walk into this 1850s farmhouse, where no one wall is straight, you cannot help but feel comfortable. This is a farmhouse that has hosted a dozen or so farm families over the years. When you sit at the table you are taking part of a ritual that unites you with the dozens of farmers that set there before. You can feel the genuine commitment, the struggles, and the determination of the many hands that farmed this land. And then, you get distracted by a rooster that jumped on the bush in front of the window and is spying on you, or the host (me) announces that it will take few extra minutes to serve dessert and points outside the other window where you can see a flock of sheep running freely down the street with the "chef" that is now running after them trying to get them back in the fences. Things are real here - we are not a "hobby" farm or a farm exclusively built for visitors - we farm. Food, hard work, love for the land and for the animals; that is why people come here and that is why strangers are not really strangers... they all have something in common and when they sit down they have a communal dining experience. At our farmhouse a meal take a few hours. Food is not a quick way to provides you with the energy enough to run to the next thing. Food IS the thing you are committed to doing. After hours or days spent preparing the ingredients and then mixing them together in authentic recipes, our only job is to be mindful of the experience and enjoy it as much as possible. Each bite. Slow down, have fun, talk and relax. No one is bringing the check to tell you it is time to clear the table for another guest. People from all ages and all backgrounds surprise themselves with something in common, laughters and chatters starts filling the rooms and the few hours go by faster than you would imagine. At our farm, this is a communal dinner. I guess I understand why some food critics are not happy with the concept of communal dining at restaurants. First of all, their main job is to criticize, and I imagine people may run out of things to write about - it may be hard to be funny and entertaining when talking positively about a restaurant and it is a lot easier to be witty and funny by complaining about something. Second, I cannot see how a sense of community can be achieved in a restaurant where people come and go at different times, meals take 30 to 40 minutes to be consumed and people may not have very much in common. There is also a different role for the people attending one of our dinner vs. customers at a restaurant. The customers at a restaurants are "consumers" of a service. People coming to our farm are partners in our agricultural community - they have an active role in supporting the type of agriculture we use and are our accomplices in working towards preserving old cooking traditions and practicing agriculture in a way that respects our animals and our land. When Stefano and I started farming we used to take long walks around the land and talk of our vision, how we wanted our farm to be. We had to compromise on the role of pigs, the amount of crops, the focus on the farm, but one thing we always agreed was that it takes a community to farm. We had no idea on how to form or find that community so instead of having a recruiting plan, we left our doors open to anyone that wanted to share a little bit of their journey with us.

We met people from all walks of life. Some never farmed before and wanted to see if that was the right thing for them. Others had a clear goal of a homestead or wanted to live the romantic slow paced life in the country (ah ah ah! It did not take us long to burst that bubble). Yet, others wanted to find their limits and figure out what they wanted from life. Our 5 bedroom farm house hosted person after person and all sorts of hands tilled the soil, pulled the plastic from the pastures, petted the pigs and shoveled a few scoops of manure. Eventually everyone moved on. Stefano and I still wondering about our idea of a farming community and still very much wanting this dream to be shared by more than just the two of us. Then here arrives katie. About 2 years ago her mother, Katie and her aunt decided to stop by the farm to drop off acorns for our pigs. As I am giving a farm tour to our 3 guests with acorns, a group of pigs decides to explore the neighbour's hay field. I start running after the pigs in the fields and katies, very naturally, follows me and helps me bring them back. A few months later Katie arrived at the farm with a box of religion and philosophy books (she is completing a BA at the University of Vermont), settled in the room with the largest king bed in the farm house, and still maintains ownership of that room. Katie also earned the farm "poop oscar" as best poop shoveler at the farm - she is very proud of that accomplishment. After 5 months from katie's arrival, Bobby sends me an email - he is an old student of mine that graduated 4 years prior. He had a good earning job as manager for a hotel chain and wanted/needed to change scene. He wanted to farm. His goal was to learn everything he could so he could buy a piece of land in Montana and farm on his own. After 5 months of living and farming with us he came in the kitchen all upset "You ruined it! You ruined the dream... I cannot buy my farm and farm alone ... farming is a community thing." And so it is... at least, our type of farming is a community thing. Don't take me wrong, there are a lot of solitary activities at the farm. Most things we do we do it independently from each other. We are always moving electric fences, cleaning the barn, watering the animals, feeding the animals. We spend so much time alone that we have started entertaining long philosophical conversations with the pigs (pigs are better listeners than sheep - we all agree). But we do not feel alone - we know someone is working in conjunction with us towards the same goal. It is like being part of an organism where each limb has its own job and independence but the final outcome is this intricate combination of detailed work. And if something cool is going on, it takes only a few minutes to reach someone and make them follow you to the place where you spotted a bobcat, or where you found a snake swallowing a frog, or to laugh at the pig that got himself stuck under a table. All the burden are lighter also when they are shared by a group of people and our own unique talents are complementary. For us, farming is definitely a community thing. Sometimes I think the level of corky-ness in my farm is unparalleled.

We had a group of 40+ students from Sterling College join us for a day at the farm and they helped us picking pumpkins from the trees (yes, you heard me correctly, our pigs planted a patch of pumpkins next to sumac trees so this year we had hanging pumpkins) and fed them to the pigs. The students were slightly surprised to see the pumpkins coming down from the trees... This is the last week the piggies stay outside and some of the small ones have already started their come back to the barn. Mostly the smaller ones – there is a group of 12 that learned to run through the electric wire as fast as they can so they do not feel the electric shock. Yes… some pigs are smart … or just rebellious, because all they did once they got on the other side was to stand few feet away from their pen and hang out there (but oh boy does freedom taste good). Never mind now they are without food water or a shelter. These are the same piglets that, once we got them inside the barn not only they got out their pen in about zero seconds (a record) but one of them decided to explore the hay loft!!! This is the first pig in the history of pigs to go up a staircase of 12 or more steps! Have you ever looked at the anatomy of a pig? Pigs are not made for stairs. They hate stairs. The only way this pig made it up there is if she took quite a bit of speed starting from the opposite end of the barn and then kept running leaping few steps at a time… an athlete, in few words. How I figured out the pig was up there? I heard weird noises from above. At first, I freaked out because what type of animal could make that noise up there? I thought of a mountain lion (of course I always think of the worst) and then I counted the piglets and a doubt started entering my head but… no… it cannot be. It was dark already so I called Stefano and the two of us slowly climbed the stairs wondering what in the world we would find up there. Yes, it was a piglet, running laps around the 20 X50 empty hay loft… She saw us and came over wagging her tail and then looked at the stairs and looked at us and it was clear from her look that she had no idea either how she got up there. Lessons about pig management you will never learn from any course on pig and pork production: how to get a pig down a set of stairs. If you look at their back legs they do not bend backward, like ours, so their back legs are useless to help going down the stairs. So …fold the back legs under the pig and let her use the front legs to get down the steps. From a human point of view it looks like a weird version of a pig-sled. But it worked. My fear is that the little piglet taught it to everyone else so, tonight, when I come home, I will see a bunch of pigs running up the stairs and then pig-sledding down like in one of those Xmas movies where they show kids sledding down white hills covered in fluffy snow. So that’s is for now from the farm where pumpkins grow on trees and pigs go sledding from the top of the hay loft. One great benefit of running a farm, or at least a farm in the north east, is that it keeps you in tune with the changing of seasons and I truly believe that I am a seasonal animal. Some people may be happier in a place where there is always a mild summer that shifts to a hot summer and then back to a mild summer. I am not. I need the hot summer, the breezy autumn, the freezing cold of winter and the crazy unsettling temperature of spring. There is something incredibly satisfying into these shifts. And let it be clear, I do not like the freezing cold (as matter of fact Stefano is happy that spring has arrived so he gets to have a break from me complaining about the cold) but it is not a matter of liking it, but rather a matter of needing it. At the farm you learn that seasons are more than a shift in temperature - there is a shift in the cycle of nature and also (forgive me for bringing in the psychologist in me) there is a shift in your thoughts and your attitude towards the world (we call it cognitive processes). From the perspective of natural cycles, Spring is the host of the most dramatic shift you can witness at our farm. Even this year when he winter was very mild for north eastern standard, you can still feel that spring has arrived with a bang! And to be specific, spring arrived last week :) All of the sudden, life is EXPLODING in all directions! Green shoots are coming out of our soil boxes, baby chicks are kicking their way into this world and lambs are popping out like mushrooms (we have piglets every month so they are less of a seasonal event for us). When I mean that life is exploding in all directions I meant, ALL, so that means that with life comes also its byproducts :) yes I mean manure!! We have manure coming out of our ears these days. Winter froze all sorts of lovely manure morsels that now are thawing but the soil is not ready to absorb this nourishment yet so the farm is transformed into this big manure storage space - with all the lovely scent that comes along with this. From he perspective of the homini sapiens at the farm, Spring is about HOPE - Spring is time to get ready for the big pasture/rotational season. We need to focus our energy and efforts on few priorities because it is only few of us and lots to do. So books about agriculture and husbandry theory and practice fill every flat surface in the house, notebooks full of ideas lie everywhere and conversations about different approaches and farming goals substitute the winter conversations about recipes and food preferences. From all these drawings and ideas grows a very well structured, organized impeccable plan that simply cannot fail! We have few more weeks before we need to have our plan nailed down for the upcoming season and then the summer dance begins. In farming at the commercial level there is very little room for mistakes. Any detail left behind has the potential for repercussions on all other levels of the system and that can easily drag you down. I am well aware that often times people are attracted to farming because of the romantic view of farmers enjoying the outdoor life, being able to stop under a tree to contemplate nature. The reality of a small farm in the beginning phases is much different from this. Indeed farming, for me, has been anything but a calming and relaxing experience - what is necessary is precision, efficiency, ability to push yourself to the limit, creative ways to look at problems and determination to get up after the nTH time you fall down. Spring is the time when you plan ahead as much as you can and you forget that every year this happens and every year Nature reminds you that it does not matter how much you prepare or plan ... stuff happens. But at least in the wee hours of the evening, when you sit down in front of your list and your spreadsheets, you have a clear, well planned farm in your mind and you better enjoy it all because that is the only time when you will see it that way :) So spring is HOPE that this year it will be different and all you have prepped for this winter and the previous year will be ready to be harvested and enjoyed.

Summer is time for DOING. We, the farmers, are not the only one "doing" each single piece of the enterprise is DOING! and sometimes doing too much! Sheep are eating eagerly the grass, grasses, plants, legumes, trees are sending our their leaves, harvesting the sun light using all the water available, pigs are exploring, harvesting, digging, growing!, chickens are searching, hunting, laying eggs and what we are left to do is to coordinate all this. It is like being the captain of a complicated ship where all the different parts of the staff do not communicate to each other. You got to do something with the grass if the pastures are growing faster than the sheep can eat, and you need to provide new safely fenced paddocks if the pigs are digging more than they are supposed to, and you need to make sure everyone has enough water and fuel to make sure they can grow at the right speed. Inevitable it comes a time when I feel I am behind and some aspect of the system is suffering. last year it was the soil. We did not have access to our equipment so we had to let some field become overgrown and that affected the soil and also the pasture quality and logically we lost feed for our sheep. Just when you feel you have attended the needs of one of the members ... inevitably the needs of another part of the puzzle are left behind. SO summer is not for thinking, summer is for DOING. Autumn is for harvesting. It is true that we harvest our meat all year around and that vegetables are harvested throughout summer, but Autumn is when you harvest considering the months ahead - it is time to anchor down. Only if the plans you made in Spring were followed and well executed you will have enough to set aside for the winter and Autumn is when you get to count what you have left in your pockets. Autumn is also time for the big roasts, the special traditional foods that keep us connected to our history and our culture. The porchetta roasts start piling up in the freezers and we start planning for the big social dinners coming up (Thanksgiving, Xmas and, for us, Cenone - New Years's eve epic dinner). WINTER - winter for me is for sleeping. I am not a person that sleeps a lot, I can happily go by with 4 to 5 hrs per night but comes winter and I become dysfunctional if I do not have at least 8 hrs. I get sleepy shortly after the sun goes down (which here in VT means it is hard for me to stay up past 7pm) and I would be completely contempt to sleep and eat the whole day. But I do have animals to attend, so I roll out of bed and go take care of the little guys across the street. Unfortunately in winter we have to work harder than before in some basic things we do not even boher with in the summer months: cleaning the barn becomes a whole day ordeal (and it is never fully clean), giving water is sometimes an epic adventure with potential for story telling for the following years (do you recall when your hair froze to the bucket of water? Or that time when you poured the whole buck on your head and it was -20 outside and almost died of pneumonia? funny stories of endurance like that...). That is the time when I always threat to raise the price of bacon :) I love pigs because when it is cold and windy, they also do not want to be bothered so at times they barely bother to get up as you put food in the early hrs of the morning (fast forward to Spring and you feel they are ready to eat you alive from how much they are screaming if you are 10 minutes late to deliver breakfast!). Winter also is time to enjoy all you have harvested during the summer and it is time for more indoor projects, and for us that means curing and preserving our meat! The natural cold temperature is perfect for making all sorts of insaccati (called in the US charcuterie). Recently I was at a pizzeria in VT with my daughter (5 yo) who noticed the place was very italian looking, or at least, very familiar to her, which I think is what prompted her to start this conversation with the waiter: "Where is your basement?" The waiter confused "The basement? You mean the bathroom?", Eva "No, the basement, you know, where you hang your prosciutto and salame for the winter?" Which makes me realize that perhaps I am succeeding at giving her an idea of what it is like to grow up Italian even in the middle of Vermont. |

AuthorFarmer Ale Archives

October 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed